TL;DR: India's diplomatic standoff with Canada exposes deep-rooted tensions between the two countries involving Sikh separatists, terrorism, crime, and historic grievances. The expulsion of diplomats and allegations of assassination marks the lowest point in Indian-Canadian relations.

Topline Points:

Diplomatic Expulsions: India and Canada expelled six diplomats each, following allegations of Indian involvement in the assassination of Khalistani separatist Hardeep Singh Nijjar, escalating tensions.

Diaspora Politics: Justin Trudeau's political reliance on the Sikh vote has compromised Canada's ability to confront Khalistani extremism effectively, leading to diplomatic friction with India.

Pakistan’s Interference: Pakistan continues to stoke the Khalistan movement to destabilize India, offering funding and support to separatist extremists within the diaspora.

Criminal Nexus: Sikh criminal gangs in Canada are entwined with the Khalistan cause, using organized crime to advance separatist ambitions while Canada hesitates to take firm action.

Long-term Damage: Canada has chosen to blame India for the extremist problem in its own backyard. While the investigations are ongoing, India Canada ties will remain severed for now.

India and Canada recently expelled six diplomats from each other’s countries. This followed Canadian allegations that the Indian diplomats, including the head of the Indian consulate, were persons of interest in a criminal investigation by the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP). The RCMP said those diplomats were ‘collecting information’ and involved in a conspiracy to target Sikh separatists seeking to create Khalistan - a proposed independent state for the Sikh religion that would break off the Northwestern part of India. The Indian government accused Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s government of supporting Khalistani separatists, and ‘smearing India for political gains’ in a strongly worded statement usually reserved for rivals like Pakistan.

Over the past 18 months, relations between India and Canada have significantly deteriorated. At the heart of this diplomatic friction lies Khalistani separatism and its entanglement with Canada’s politically powerful Sikh diaspora - over 770,000 Sikhs live in Canada, the largest population of Sikhs living outside India. In September 2023, Trudeau publicly accused India of involvement in the killing of Hardeep Singh Nijjar, a Khalistani separatist and gangster wanted on terrorism-related charges in India. US authorities claimed they had foiled a separate plot against Nijjar’s lawyer: Gurpatwant Singh Pannun, an American citizen and leader of Sikhs For Justice - a self proclaimed ‘civil rights group’ organizing unofficial referendums for Khalistan within the global sikh diaspora. Pannun has also filed suit against Indian officials in the Southern District of New York.

The Indian government has consistently denied all allegations, and has continued to demand hard proof from both Canadian and American intelligence agencies. Earlier this week, the State Department announced the visit of an Indian delegation to America to cooperate in this ongoing case with their American counterparts. Later, the Indian government informed the DOJ it had arrested the former intelligence officer named in the indictment.

The diplomatic spat with the Canadians is ongoing, who have now resorted to claiming that India’s crime is monitoring separatist activities inside Canada. The Canadians have also leveled vague accusations that Indian intelligence is using criminal gangs inside Canada to gather information about these separatists, a dubious charge considering India has repeatedly requested the extradition of these same criminals.

Trudeau’s domestic position is unstable amid mounting calls for resignation from his own party - Jagmeet Singh’s NDP withdrew its support from Trudeau’s coalition government in September. Singh, the most prominent Sikh politician in Canada has ambitions of his own as he seeks the prime ministerial seat in the next federal election in Fall 2025. Trudeau’s declining popularity and potential resignation may hasten that timeline. His attempt to revive a year-long diplomatic fight with India must be seen in this context. This is not the first time Trudeau has pandered to the Sikh voters of Canada. His embarrassing trip to India in 2018 resulted in his first diplomatic row with India, when it was revealed his office invited a convicted Sikh terrorist to dinner in Mumbai.

For most of my American friends, the Khalistan issue is a mystery. Their understanding of the Sikh community stems from their martial fame and well-earned reputation as loyal soldiers who fought for King and Country during the two world wars. To be clear, most Indian Sikhs do not support the Khalistan project, and most ‘Khalistanis’ live outside India among the diaspora in America, UK, Canada, and Australia. While a small faction of religious extremists are vocal advocates for Khalistan, there is an overlap between the violent extremists, the politicians seeking votes, and ordinary Sikhs protective of the Sikh diaspora identity. The Indian government and India’s political parties have maintained a firm position on the country’s territorial integrity, shaped by the history of ethnic and linguistic separatism in the subcontinent.

To truly unpack this complex and still unresolved-story, it’s important to start at the beginning.

The roots and beginnings of Sikhism

Sikhism, that is the Sikh religion, has its roots in the 15th century in the region called the Punjab — the land of the five rivers. Now divided between Pakistan and India, the Punjab remains one of the most fertile parts of North India. By the 15th century, the region had been settled by Iranians and Turks alongside the indigenous population of Hindus. Both Islam and Hinduism were experiencing political and social upheaval. Preachers, mystics, and godmen were prevalent in India and across Punjab. One of them was Guru Nanak, whose teachings formed the tenets of what became Sikhism. Guru Nanak preached that there was neither Hindu nor Muslim, and that all people were one. His emphasis on the concept of Ik Onkar (One Supreme Reality) rejected both Hindu polytheism and Islamic dogma. His egalitarian teachings challenged the rigid hierarchies of the Indian caste system and resisted Islamic conversion, attracting numerous followers in Punjab.

The concept of the gurus (teachers) is central to Sikhism. Successive gurus after Guru Nanak built on his teachings to form a distinct Sikh identity. Guru Arjan compiled early Sikh scriptures into what would eventually become the Guru Granth Sahib, the authoritative holy book for Sikhs. He was also the first Guru to be martyred, tortured to death by the Mughals, becoming a powerful icon of the faith. The tenth Guru, Gobind Singh, established the Khalsa, which gave Sikhism its martial nature through a baptism ritual (khande di pahul) and strict code of conduct (rahit maryada). All Sikhs initiated into the Khalsa were to be known as Singh (Lion). A separate script, Gurmukhi was created to give Sikhism its own writing system and promote self-identity. Eventually the Sikhs created their own empire in the Punjab, until it was annexed by the British in 1849, following the defeat of the Sikh forces in the Second Anglo-Sikh War.

So far, this is the traditional World Religion 101 narrative of Sikhism you will read in most texts. In reality, the development of Sikhism was much more complex and syncretic with the Hindu faith. The diversity of Punjab’s clan, caste, and local networks precluded the immediate rise of a scriptural monotheistic faith, and indeed most people in the region moved between multiple identities depending on the time and place.

According to Giorgio Shani in Sikh Nationalism and Identity in a Global Age: ‘A visit to the Ganges or to the shrine of a Muslim saint was as much part of the devotional life of most Sikhs as a visit to the Golden Temple.’ The Sikh faith was a “fuzzy, unenumerated community consisting of not only Khalsa Sikhs or ‘Singhs’ but a multiplicity of other traditions which were, in some cases, indistinguishable from Hinduism.”

Sikhism and the Raj

Over the centuries, Sikh leaders worked to purify the faith — purging syncretic practices and reinforcing the Khalsa identity, with its distinct religious markers like uncut hair and the ceremonial sword. This differentiation was not just religious but political, as Sikhs sought to safeguard their traditions against the perceived threat from Hindu reform movements that sought to merge Sikhs back into the Hindu fold. This move towards a hegemonic identity was aided by the British need for dependent and obedient soldiers, which meant encouraging the martial Khalsa identity among the Sikhs of Punjab and service with the army as a path to social mobility. Paradoxically, the British also cultivated loyalty among the syncretic non-Singh mahants who controlled many gurdwaras and holy shrines of Sikhism. The mahants were more like Shinto hereditary families who managed religious sites, rather than strict guardians of the faith like the ulema in Islam — and were thus unable to counter the Khalsa orthodoxy.

In Religion and the Specter of the West, Professor Arvind-Pal S. Mandair of the University of Michigan explores the evolution of Sikhism as it came into contact with the West. Mandair argues that Sikhism’s classification as a monotheistic religion emerged through colonial translations and reforms, particularly under the Singh Sabha movement. This reform movement sought to distinguish Sikhism from Hinduism by emphasizing the monotheistic worship of a singular, eternal God. Influenced by western theologians and reformers who framed polytheism as ‘backward’ Sikh reformers rejected pantheism, insisting that Sikhism adhered to monotheism to legitimize their religion in the eyes of colonial rulers.

By the early 20th century, Sikhs were disproportionately represented in the British colonial forces, both the military and the police. Whether because of pseudo-sociological beliefs, or antipathy to polytheism - all Sikhs joining the British regiments were required by the British to undergo the khande di pahul: baptism into the Khalsa, with the belief that any reversion to Hinduism would result in ‘loss of martial instincts.’ Ethnic and linguistic nationalist movements were on the rise in Europe, and India wasn’t far behind. Urdu, Bengali, Tamil, Gujarati, and Marathi nationalists formed identity and interest groups to lobby the British and safeguard their cultures. The colonial extractive impulse meant demarcating and crystallizing the earlier ‘fuzzy’ identities for the purpose of records and censuses. Before the colonial period, the belief among Sikhs was that they constituted a separate panth - a distinct spiritual community. By 1900, the narrative shifted to describing the Sikhs as a separate qaum - an Arabic word meaning a political community, or a nation. The blurred lines between Khalsa and non-khalsa sikhs, and sikhs vs. hindus had become clear and created a path for a systemic social and institutional takeover.

In 1925, a reformist push called the Akali movement wrested control of Sikh gurdwaras and shrines from the hereditary mahants by lobbying the British government. This led to the rise of the Shiromani Gurdwara Parbandhak Committee (SGPC), established to manage Sikh religious institutions and play a central role in Sikh political and religious affairs. In the basic texts of Sikh history, this takeover by the Khalsa is portrayed as a resistance movement by patriotic Sikhs against the corrupt mahants who were loyal to the British, once again cementing the idea that true Sikhs protect the faith from outside and within.

Since then the SGPC and its political wing, the Shiromani Akali Dal (SAD) have been the hegemonic institutional and political expressions of Sikh identity in India. Their takeover also institutionalized the Sikh identity, by defining who was and was not a proper Sikh, resulting in the effective outlawing of the more syncretic Sikhs - one could now only be a true Sikh by undergoing baptism and conforming to the Rahit Maryada. The other outcome of this takeover was the idea of ‘territorialization’ of the Sikh identity as uniquely linked to the land of Punjab. The Sikhs were the ‘lions of Punjab’ who had defeated the Afghan invaders, resisted the British in successive wars, and formed the backbone of the colonial armies in the decades since.

Sikhs were prominently involved in the struggle to free India from the British yoke. The most famous Sikh from that period is Bhagat Singh, a 23 year old socialist revolutionary who was hanged by the British. Singh - often referred to as Shaheed, (martyr) remains an icon of the struggle and sacrifice by young men to create a free India. The other revolutionary group of that time was The Ghadar Party. Formed by Indian expatriates in North America, the Ghadar Movement sought to end British rule in India through armed revolt. Many of its members were Sikh farmers and laborers in the United States and Canada. Though the Ghadar Movement was unsuccessful, its role in diaspora Sikh identity was important, as it fostered a strong sense of political activism and resistance for the faith.

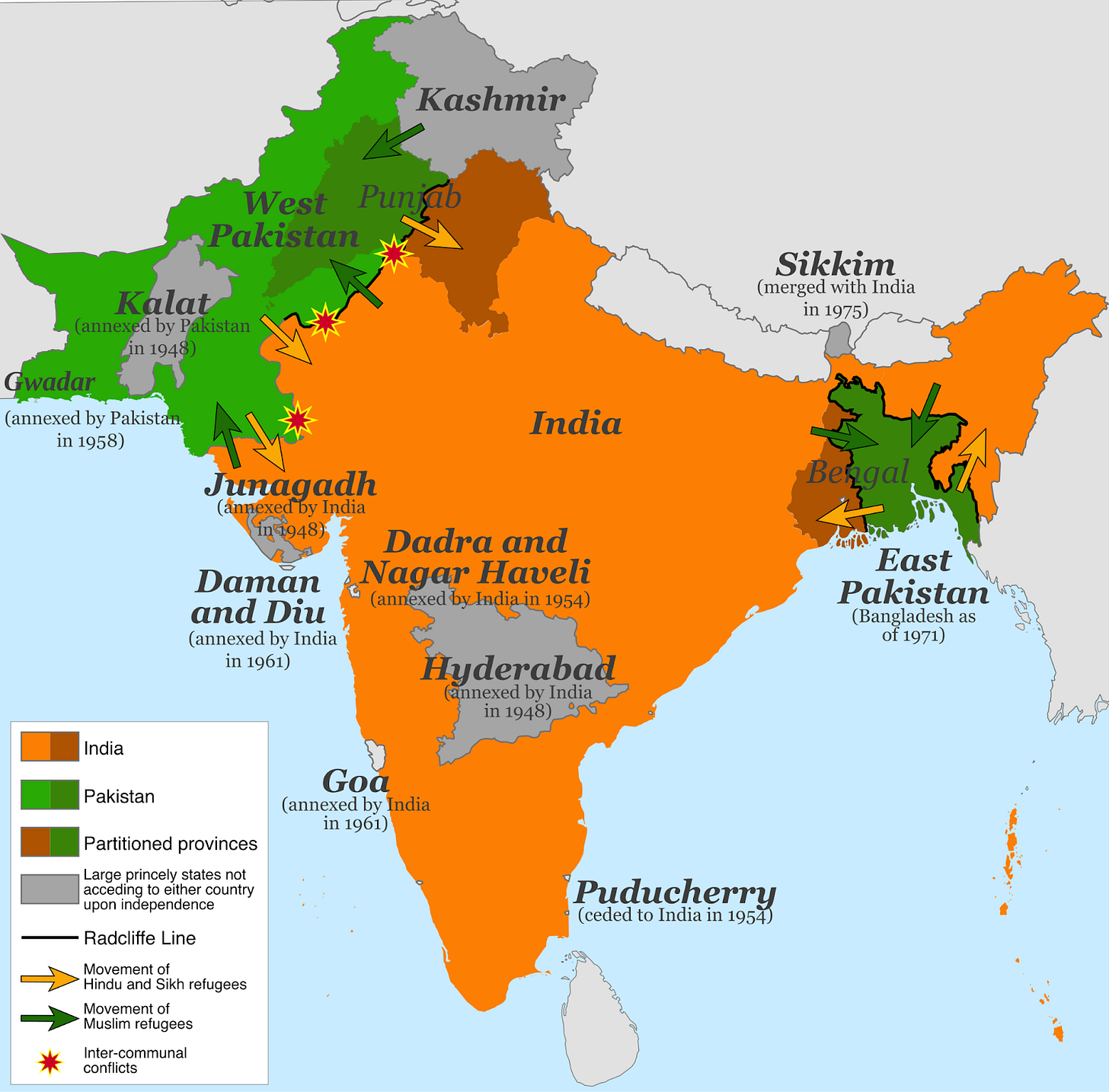

As the British retreated from India, nationalist ideas which had been bubbling for decades came to the fore. Many intellectuals advocated for political sovereignty for Sikhs in a separate nation, including the SGPC who wanted to ‘preserve the main Sikh shrines, Sikh social practices, Sikh self-respect and pride, Sikh sovereignty and the future prosperity of the Sikh people’ (SGPC 1946). Unfortunately the winning argument was the demand for Pakistan (Land of the Pure) by the Muslim League - its political lobbying, strength and demonstration of street power ultimately resulted in the division of the Punjab and Bengal provinces between two nations: India and Pakistan. The initial argument for Khalistan was to protect the Sikh faith from a militant Islam - ironic, considering how large Hindustan (Land of the Hindus, an old name for India) looms in the imagination of Khalistanis, and how muted Khalistanis are today about the subject of Pakistan.

Punjab and the Indian state

The trauma of partition cannot be fully expressed or explained in a paragraph or two. Suffice it to say, the violence and upheaval of 1947 only strengthened Sikh self-identity. Many refugees from Pakistani Punjab settled in Indian Punjab and New Delhi, forever cut off from the land that had been theirs for hundreds of years. To make matters worse, the arbitrary drawing of borders meant Kartarpur Sahib and Nankana Sahib, two of the holiest sites in Sikhism, were now in Pakistan. Sikh leaders were outraged at the lack of consultation with the Sikh community regarding the drawing of the borders. India’s wars with Pakistan over the decades meant that Sikhs on the Indian side could see their holiest shrines only from afar, or by special visas, reinforcing their aggrieved feeling of being minorities in both countries.

This period of trauma only reinforced the Sikh community's belief in political autonomy. The Akali Dal launched campaigns demanding a Sikh-majority state within India, which culminated in the creation of Punjab as a separate state in 1966. The fight for Punjab, recognition of Gurmukhi and the Punjabi language by the Indian government, and competition with other communal groups within India gave Sikh activists the feeling that they were fighting a dharm yuddha (war for the faith). The sacrifice of Sikh soldiers in the wars against China and Pakistan proved their martial quality once again within the context of Indian national identity. However, many Sikhs felt marginalized, and tensions between the Sikh community and the Indian government only grew worse.

Punjab is an agrarian region — its fertile soil supporting a predominantly farming-based economy for centuries. Known as the "granary of India" even before independence, its people have long relied on agriculture as their primary livelihood. After independence in 1947, Punjab's economy remained largely agrarian, with most of the population engaged in farming. Though Sikhism preaches equality and rejects the caste system, caste identities persist within Sikh society. In Punjab, the Jatts are traditionally farmers—who remained dominant in rural areas, controlling much of the land and the agrarian economy. Khatris were more involved in trade and business, and thrived in urban Punjab. There are also lower castes who traditionally occupied marginalized roles: Mazhabi Sikhs ("untouchables" before converting to Sikhism), and Chamars, who were historically associated with occupations like leatherworking, and sanitation. Despite Sikhism’s rejection of caste hierarchy, these groups often faced social and economic discrimination, with limited access to land ownership or upward mobility compared to Jatts and Khatris.

In the 1960s, Punjab underwent the Green Revolution — an era of agricultural growth and prosperity for the region. American scientist Norman Borlaug developed high-yield, disease-resistant wheat varieties and advocated for their use in Punjab, averting India’s fears of famine. The success of the green revolution, and government largesse for the agricultural breadbasket of India largely benefitted the Jatt agrarians, causing wealth and income disparities. The feudal structures of Punjab remained - urbanization and modernity only contributed to a disenchanted, and resentful labor class.

In the years following independence, India saw the rise of several ethnonationalist movements. Inspired by Muslim nationalism’s success in creating Pakistan, these movements sought autonomy on linguistic, religious, or regional identity, challenging the notion of a unified Indian state. India’s own post-independence identity was unclear - it was led by Jawaharlal Nehru, a Fabian Marxist educated at Cambridge who imposed his flavor of secularism and state socialism on the country. These separatist movements threatened to balkanize a multi-ethnic, multicultural, multi-linguistic state with an inherited colonial political system. Most of the separatist movements were eventually defanged and delegitimized as India’s democratic institutions matured and an Indian national identity emerged. But the most dangerous of these movements which threatened India’s territorial integrity was Khalistan.

Khalistan

Indira Gandhi was the daughter of Jawaharlal Nehru, independent India’s first Prime Minister. More autocratic and populist than her father, she succeeded him as PM in 1966 after a brief interregnum. Gandhi gathered power through socialist policies like land reform, nationalizing banks, and anti-poverty programs. A war with Pakistan in 1971 resulted in an Indian victory, and the creation of Bangladesh - resulting in massive popularity for her. The moniker Henry Kissinger bestowed on her, “Iron Lady” was apt. Accused of corruption and convicted of electoral malpractice, she was ordered by an Indian court to step down — an order she refused. Mrs. Gandhi instead declared a national emergency, imposed martial law, jailed her opponents, and consolidated power. After a brief period between 1977-1980 when she stepped down, she was able to collect popular support by using the specter of foreign interference and by portraying herself as the savior of the nation. Indira was elected again in 1980 to lead a national government.

It is in this context that Mrs. Gandhi’s engagement with the Sikh community and the SAD (Shiromani Akali Dal) party must be viewed. When presented with the Anandpur Sahib Resolution, a series of demands for greater Sikh autonomy, economic redistribution, and recognition of Sikhism as separate from Hinduism - she interpreted it as a secessionist demand. To force the central government to accept the resolution, the Akalis marched in force, blocked roads and railways, and mobilized the Sikh population.

It was Mrs. Gandhi who lit the slow fuse of Khalistan by nurturing Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale and other extremists to undermine the Akali Dal. Bhindranwale was an extremely orthodox Sikh, who spoke “in a religious vocabulary steeped in the symbolism and mythology of the Khalsa”. Bhindranwale also joined in the demands for the ASR, and drew on the memory of martyred Sikh Gurus to declare war against enemies of his religion. Bhindranwale gathered support by playing up Sikh identity politics and by deploring the ‘other’ — that which lay outside the panth - television, alcohol, tobacco, atheism, and Hinduism. He preached that all amritdharis(baptized Sikhs) should be shastradharis(armed Sikhs). Punjab’s marginalized Sikh youth flocked to his cause - militancy and violence soon destabilized the state. The Indian police’s heavy-handed response caused retributive acts of violence against Punjab’s Hindu population, and Hindus also began to organize self-defense militias. An internecine war on the doorstep of India’s capital loomed. Despite negotiations, talks between Bhindranwale and the Indian state broke down. He refused to budge on the issue of the Anandpur Sahib Resolution, and felt he would be betraying his sacred word by watering down his demands.

Bhindranwale moved into the Golden Temple in Amritsar, the location of the temporal authority of the Sikh Religion, and its holiest site. Bhindranwale immediately formed a revolutionary government with himself as the head and dispensed vigilante justice. According to journalist Terry Milewski in Blood for Blood: “bodies, mutilated, hacked to pieces, stuffed into gunny bags, kept appearing mysteriously in the gutters and sewers around the Temple. The shrine, whose image can be found in every Sikh home, in every Sikh heart, had been transformed into a place of torture and of execution.”

In June 1984, Indira Gandhi initiated Operation Bluestar — the Indian army was ordered to storm the temple by force. Bhindranwale and his followers died in the ensuing firefight. By the end, the Indian army had shelled the temple complex with artillery and raked it with machine gun fire, an act of desecration and a trauma equal to that of Jallianwala Bagh in 1919 - when a British general ordered Indian troops to open fire at an unarmed crowd in Amritsar, Punjab. In the eyes of many Sikhs, Bhindranwale had become a sant — a saint who martyred himself for the faith.

Diaspora Sikhs were outraged. Indira Gandhi was burned in effigy in Sikh protests around the world. In July 1984, the World Sikh Organization was convened at Madison Square Garden in New York City. One of the keynote speakers was Ajaib Singh Bagri, who would later be accused and acquitted of the Air India 182 bombing that killed over 300 people. Bagri’s rhetoric was fire and blood, with repeated calls for Indira Gandhi’s assassination and hatred for Hindus.

On October 31, 1984, Indira Gandhi was assassinated by two of her Sikh bodyguards. Her son Rajiv Gandhi succeeded her as Prime Minister. A series of organized pogroms led by Gandhi’s supporters occurred in North India, in which Sikhs were attacked, brutalized, and murdered. The official death toll is over 3,000 Sikhs murdered. Rajiv Gandhi’s callous response was unhelpful: “When a big tree falls, the earth shakes.” A government commission created in 2000 to investigate the 1984 riots placed blame on senior members of the Indian National Congress party. The known perpetrators of these pogroms remain free, except one.

The trauma of Operation Blue Star and the 1984 riots reshaped how the Sikh diaspora engaged with the world. Its alienation from the Indian state was complete. It deterritorialized the concept of the Sikh community from India, and reterritorialized it within the diaspora identity. Even among non-Khalistani Sikhs, the concept of Sikh sovereignty and the panth was now tied to diasporic, globalized networks of solidarity. The concept of miri-piri (spiritual and material responsibility) is central to understanding Sikh participation in politics and minority activism, where they often punch above their weight, and vote as a community. In addition to political activism, responsibility means advocating for Sikhs in global communities and joining in solidarity with social justice organizations. An added benefit: it aligned the Sikh struggle to progressive advocacy for anti-racism, anti-fascism, anti-imperialism, and immigrant rights.

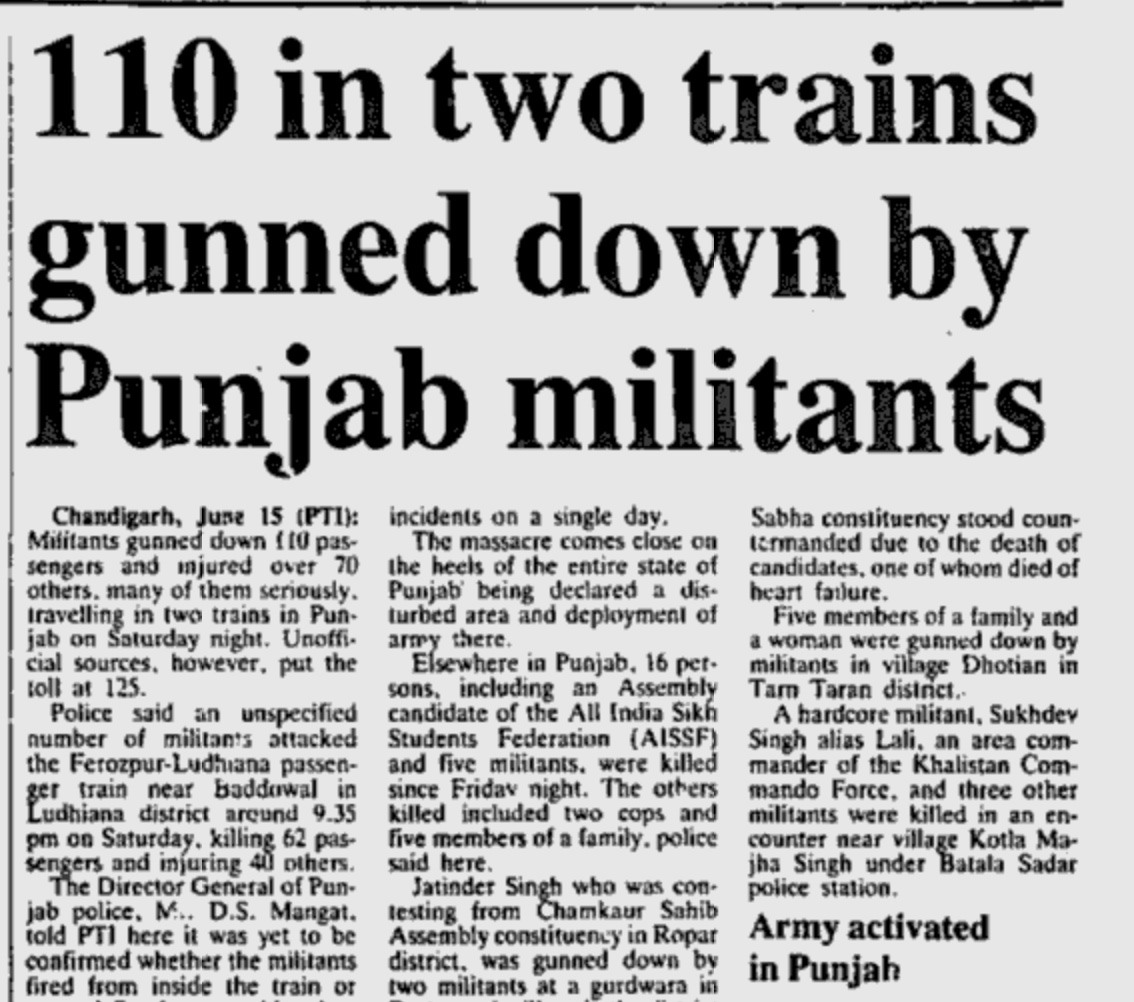

In press statements, Bhindranwale had demurred on the idea of seeking Khalistan — his focus was the adoption of the ASR. After 1984, peaceful negotiation with the Indian state was impossible. Punjab became the center of a full-blown insurgency. With support from Pakistan and the Sikh diaspora — the movement for Khalistan became real. AK-47s, bombs, and men were ferreted across the porous Punjab-Pakistan border. Assassinations, robberies, and kidnappings became commonplace. Morale in the Punjab police force — many of whom were Sikhs — plummeted as their religious leaders condemned any Sikh co-operating with the Indian state. The state’s response was feeble, and wary of repeating the incompetence of Operation Blue Star.

The Khalistan insurgency faced its most significant blow under the leadership of KPS Gill, a Sikh police officer who spearheaded a relentless crackdown on militancy in Punjab during the 1990s. Gill’s approach was aggressive counterinsurgency tactics, which broke the back of the Khalistan militancy and restored relative peace to Punjab. Gill had his critics, and accusations of human rights abuses — but his leadership was decisive in ending the militant phase of the movement. In 1996, the Shiromani Akali Dal joined the BJP in forming a government at the center, signaling the return of normalcy to Punjab. Since then, Sikhs have continued to play a prominent role in India’s successive governments and military leadership. India’s 13th Prime Minister was Manmohan Singh, a proud Sikh and a member of Indira Gandhi’s Indian National Congress party. Singh’s official apology as Prime Minister for the violence of 1984 was the right move in healing the trauma of India’s Sikh community.

The continued success and involvement of Sikhs in the Indian state is a source of resentment from members of the Sikh diaspora who support the Khalistan cause. To this day, they see such Sikhs as traitors to the community. For them, the end of the Khalistan insurgency in India represents a defeat not just of a political cause, but of an identity-based struggle that they feel is yet unfinished. This unresolved resentment fuels separatist sentiment among some Sikh communities, particularly in countries like Canada, where they continue to advocate for Khalistan.

Pakistan’s Quest for Revenge

Pakistan’s interest in Khalistan is not new—it dates to the 1971 Bangladesh Liberation War. In the east and the west, India defeated Pakistan and played a key role in the creation of Bangladesh — effectively dismembering Pakistan. For Pakistan, supporting Khalistan was revenge, a means to destabilize India from within, much as Pakistan felt India had done to them during the Bangladesh war.

For decades, Pakistan’s intelligence services, particularly the Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI), have covertly supported Khalistani separatists, providing them with arms, funding, and safe havens. While the movement was largely crushed within India, Pakistan continues to provide backing to extremist elements in the Sikh diaspora as part of a broader strategy to undermine India’s internal stability. In 2006, a Pakistani national Khalid Awan was sentenced to 14-years imprisonment by the DOJ for Providing Material Support and Resources to the Khalistan Commando Force (KCF).

In an interview with Canadian author Terry Milewski, former Ambassador Husain Haqqani said the following about Pakistan’s involvement, “Pakistan also wanted to create a strategic ‘buffer’ between India and Pakistan. Such a buffer state, Haqqani says, would ‘end India’s land access to Kashmir’ – and Kashmir was and is a perennial focus of Pakistani policy.”

Today, Pakistani voices on social media often speak of the imagined unity of the Punjabi speaking Muslim elite of Pakistan with the Sikh community of Pakistan before 1947 — these accounts claim partition was the fault of the British, and share propaganda about the Sikh community’s oppression in India. The opening of the Kartarpur corridor in 2019 was another opportunity for Pakistan to signal amity with Khalistan and the Sikh diaspora. Promotional videos from the Pakistani side contained prominent images of Bhindranwale.

Air India 182

In June 1985, a bomb planted by Khalistani terrorists on Air India Flight 182 exploded, causing the death of all 329 people on board. It was the largest aviation-related act of terrorism until 9/11. A colossal intelligence failure on Canada’s part - Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau’s government had been warned by India’s intelligence agencies that an attack was imminent. In response, Canadian intelligence removed its mole from the bomb plot to avoid implicating him. The mastermind of the AI 182 bombing was Talwinder Singh Parmar, who returned to India after the bombing and died in a firefight with Indian police. He is still celebrated in Canadian gurdwaras as a martyr, and NDP leader Jagmeet Singh had to walk back his vague non-answer when asked to condemn the glorification of Parmar.

Despite overwhelming evidence, pro-Khalistan groups have always disavowed the role of Sikh nationalists in the bombing, and blame Indian intelligence for planting the bomb. After multiple arrests and trials, only one person was convicted in the bombing. 39 years later, the RCMP admits that the investigation into the bombing is ‘still ongoing’ providing no closure to the surviving family members of the victims. One wonders what new evidence they could dredge up from the Atlantic Ocean after 40 years, or whether there’s political pressure from the top to prevent conclusions that would point straight at an active extremist group supported by vote bank politics. Incidentally, 9 out of 10 Canadians have never heard of the deadliest air attack before 9/11 that killed over 300 Canadian citizens.

Trudeau’s Political Quagmire

Sikhs are dominant in at least 10-20 ridings (constituencies) in Canada, and politically important in major provinces of Canada. During election season, major politicians from all parties visit Gurdwaras (Sikh places of worship) to court the Sikh vote. And in the next federal election, the Sikh politician most likely to challenge Trudeau for the Prime Minister’s seat could be the NDP’s Jagmeet Singh.

Singh, leader of Canada’s New Democratic Party (NDP), is a prominent Sikh politician. While he has not openly advocated for Khalistan, he has refused to condemn it or its adherents. For Indian policymakers, Singh’s associations, his prominence in Canadian politics, and his vocal anti-India rhetoric are a tacit endorsement of Khalistani separatism. Prime Minister Justin Trudeau has relied on Singh’s NDP for political support in his government, making it even more difficult for Trudeau to take decisive action against pro-Khalistan elements. Singh’s latest statement on the October 2024 tensions supports Trudeau’s actions to expel Indian diplomats, and includes a call to ban the RSS in Canada. The RSS is a Hindu volunteer organization in India that supports Prime Minister Modi. It reveals Jagmeet and Canadian Sikh extremists' true motives — the delegitimization of Hindus, Hindu advocacy, and expulsion of any Hindu political expression from the public sphere.

Trudeau’s unwillingness to confront these separatist groups, along with his reliance on Singh, has been a source of frustration for India. It has led to an escalating war of words between the two nations, with India accusing Canada of harboring terrorists and Canada accusing India of monitoring Canadian citizens to create ‘transnational repression’. As for Khalistani rhetoric, Trudeau and his party frame it as maintaining Canadian commitment to democratic freedoms, including the right to political expression. Even now one can visit a random gurdwara in America, Canada, or the UK and encounter Bhindranwale’s image next to the image of the Sikh gurus. This has caused headaches for Indian diplomats, especially those of the Sikh faith who wish to visit and pray with the Sikh diaspora.

“...open reverence for dead killers has been a consistent feature of the Khalistan movement. No matter how innocent their victims and no matter the damage done to the killers’ own cause, the routine is the same: a picture of them posing with a gun is framed and hung on the wall in a gallery of martyrs.” (Blood for Blood, Terry Milewski)

The murder of Hardeep Singh Nijjar re-opened decade long grievances between India and Canada. Gunned down by unknown men in 2023, Nijjar was a known Sikh extremist and criminal, who arranged weapons training for fellow Khalistanis, had been put on the Canadian no-fly list and had an Interpol red notice out for him. In 1995 “Mr. Nijjar fled Punjab shortly after a bomb…tore through the bulletproof white car belonging to Punjab’s chief minister, Beant Singh, killing the 73-year-old and 17 others.”

Over the past few decades, Sikh criminal gangs operating in Canada have become entangled in both separatist politics and organized crime. These gangs are involved in everything from drug trafficking to targeted killings, and some of their members have links to pro-Khalistan networks. Apart from criminal activity in Canada, these transnational gangs also operate in India and the United States. In 2022, the murder of Canadian Sikh Rapper Sidhu Moose Wala was linked to Goldy Brar, a rival gangster. Brar arrived in Canada in 2017 on a student visa, and took leadership of the Bishnoi gang operating there. Brar was also associated with the Babbar Khalsa, another Khalistani offshoot “involved in multiple murders, arms and ammunition smuggling, and fomenting radical ideology.”

Though the Indian government has repeatedly expressed concerns about Canada’s inaction against these criminals, the Trudeau government has been reluctant to take stronger measures. Extradition requests have not been honored, or concerns are raised about India’s judicial system to deflect from the issue. This reticence is partly due to Canada’s internal politics, where the Sikh community holds substantial influence, and any crackdown on Khalistani groups risks alienating a key voting bloc. In 2019, a Canadian report that listed “Sikh Extremism” as one of the top 5 threats to Canada was watered down after lobbying from Sikh groups concerned that the report was targeting the Sikh religion.

Months after Nijjar’s murder, Justin Trudeau rose in the Canadian Parliament and accused the Indian government of orchestrating Nijjar’s murder. The American DOJ also accused a member of India’s intelligence service the R&AW (Research and Analysis Wing) of plotting to kill Nijjar’s lawyer Gurpatwant Singh Pannun, who is an American citizen.

In addition to his association with Nijjar, Pannun is a ‘lawyer’ for the pro-Khalistan group Sikhs for Justice. Pannun is an odious and insufferable loudmouth, who never misses an opportunity to unleash bitter, venomous tirades on anyone unfortunate enough to cross his path. He frequently accuses Hindus in India and Canada of ‘dual loyalties’ and flaunts dubious connections with government insiders in both countries. His tirades are directed at Indian Prime Minister Modi, Indian diplomats, Indian politicians, and Hindus, all of whom he has threatened and demands that they leave Canada.

One of the weasel words used by pro-Khalistani extremists is that they’re simply advocating for justice using their free speech rights. This free expression includes parade floats celebrating the assassination of Indira Gandhi, posters celebrating Khalistani mass killers outside Gurdwaras, doxxing Indian diplomats and threatening a Hindu-Canadian Member of Parliament. After the most recent diplomatic spat between Canada and India, Sikhs for justice uploaded a video of a poster of India’s highest ranked consular official to Canada being shot by a gun.

Khalistanis have also been active in the United States, using visits by Indian officials to vandalize local Hindu temples. In September 2024, they vandalized a Hindu temple in New York, and earlier in 2024 a Hindu temple in California was similarly defaced with pro-Khalistan graffiti. In 2023 Khalistanis tried to firebomb the Indian consulate in San Francisco using the cover of a protest on the street outside.

The Activism Playbook

Muslim and Sikh diaspora organizations often define their engagement in the West by importing political divisions from the Indian subcontinent and framing the Hindu diaspora as an existential threat. A common tactic is accusing Hindus of dual loyalty, tying them to the policies of India’s current political regime, which is labeled as nationalist or fascist. They’ll appropriate the language of the home country, with activists concern trolling about Hindu incompatibility with “Canadian values”, suggesting all diaspora Hindus engage in caste discrimination, and use Hinduism’s polytheistic nature to scare American Christians. It gives cover to internal issues within Muslim and Sikh communities, such as crime, extremism, and factionalism. Hindu communities are scrutinized for political and cultural affiliations, while similar issues within other communities are downplayed. This projection is often coupled with a narrative that frames Hindu prosperity and political engagement as inherently problematic, associating any success with support for a nationalist agenda from India.

These organizations align their messaging with progressive discourse, invoking anti-racism, anti-hate speech laws, and Islamophobia to shut down any criticism of their own communities - while casting Hindus as the interlopers. In this dynamic, Hindus find themselves caught in a difficult position. As a community that values assimilation and prosperity, Hindus are less inclined to engage in aggressive identity politics, making them more vulnerable to accusations that they are aligned with far-right ideologies. This places Hindus at a disadvantage in the public discourse, especially when their success is framed as a sign of complicity in transnational political agendas. It not only perpetuates historical political divisions but also unfairly casts Hindu communities as symbols of oppression, making Hindus fair game for an imagined ‘resistance’.

Normalization of terrorism and glorification of violence is evident from even a cursory glance at pro-Khalistani accounts. The Khalistani narrative frames their violent actions and rhetoric as a continuation of anti-colonial struggle, linking it to the historic Sikh resistance against oppressive regimes, such as during the time of Maharaja Ranjit Singh or the British Raj. They’ll also blame exposure of their militant ideologies as part of a conspiracy orchestrated by the Indian state. It allows activists to both promote hostility and violence while claiming to be victims of government plots whenever their rhetoric is exposed or challenged.

Diaspora Sikhs who are disconnected from the realities of modern India and Punjab are drawn to simplified narratives of heroism and resistance that do not reflect non-violent participation in India’s politics by the Sikhs of India. This disconnect is symptomatic of an identity crisis, in which the glorification of Khalistani violence is a symbolic substitute for the loss of cultural roots and an idealized vision of a homeland they have little connection to.

Sidhu Moosewala, the slain rapper from Canada, had gone to Punjab to enter its local politics. Moosewala’s songs and music videos popularized gangster culture in Punjab and glamorized crime associated with Khalistani gangs. Moosewala and other Punjabi rappers sing songs that boast about making money illegally, violence against rivals, or the objectification of women - these songs reflect a criminal ethic, more than an ethos of resistance. One wonders how Moosewala and other rappers would have been treated by Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale, who had no love of earthly pleasures.

Another ignored factor in the Khalistan issue is casteism. Many Punjabi rap songs that are popular worldwide, like Moosewala’s ‘Jatt Da Muqabla’ glorify the Jatt caste of Punjab. The lyrics in these songs frequently celebrate the Jatt caste identity through themes of physical strength, fearlessness, and social domination. Singer Diljit Dosanjh who played at Coachella in 2023 became famous for his song ‘Jatt Fire Karda’ (The Jatt Fires His Gun) - BBC Asia banned the song in 2015 for its celebration of violence and gun culture. This blend of revolution with the consumerist celebration of fame, wealth, and criminality, is a globalized, commodified resistance that undermines its own ethical foundation.

It shifts focus away from the real challenges abroad and at home such as unemployment, the drug epidemic, and agrarian distress in Punjab, which have plagued the state for years. Perhaps the ignorance is by choice, since the Jatt agricultural elite of Punjab have resisted reforms that would benefit the marginalized castes of Punjab. The 2019 Farmer protest, which was supported by Trudeau and the Sikh diaspora was one such Kulak protest, and emblematic of the entrenched attitude by the diaspora - most of whom are Jatts themselves.

The fault, dear Brutus

To summarize: Canada claims India is undermining its sovereignty, branded as ‘transnational repression’. Yes, the real threat to Canada’s integrity is from the Indian state. This is despite the Air India 182 bombing, the murder of key witnesses, the murder and brutalization of journalists, assassinations, gang wars, and open threats made against Hindus and government officials. But according to Justin Trudeau, it’s India that Canadians should be worried about.

If the diplomatic row between India and Canada continues, the closing of consulates and ordinary diplomatic business will only hurt Canada and members of the diaspora. Should Pierre Poilievre win the next federal election, he will be left to repair the damage. The Canadian RCMP will have to examine its own role in fighting extremism and serious gang activity in Canada. Canada’s intelligence agencies should also re-examine the presence of Pakistani and Chinese intelligence operations.

The investigation by the DOJ and FBI in the Pannun plot is ongoing. American officials have thanked India for its cooperation in the matter, displaying how diplomatic relations are handled in the absence of a bloviating, self-serving leader. The long-term damage to Indian-Canadian relations may hinge on Canada's ability to acknowledge and address extremism among its citizenry. One solution that has resonated with the Indians is AEI scholar Michael Rubin’s call for India to designate Canada as a state sponsor of terror. That may well be what happens.

This is not to suggest that India is without fault, nor an excuse for the lunatic actions of an Indian intelligence officer who believed he could orchestrate a secret assassination in America. While Sikh advocates are right to demand accountability for attacks emanating from India, they have to be willing to confront extremism and aggression within their own communities. No country would quietly overlook or tolerate separatists who threaten to ‘balkanize India’ — even from a clown who parrots meaningless slogans.

The Khalistan insurgency took the lives of over twenty-thousand Indians. The lesson India learned about the fragile nature of a pluralist democracy came at a high cost. The strong response by India to Canadian provocation repeats that lesson clearly: India’s national security and sovereignty are non-negotiable, even at the cost of severing diplomatic ties.

Further Reading/References

Terry Milewski. "Khalistan’s Deadly Shadow." Quillette, 28 Apr. 2018, https://quillette.com/2018/04/28/khalistans-deadly-shadow/.

Pande, Aparna. "Pakistan’s Destabilization Playbook: Khalistan Separatist Activism Within the US." Hudson Institute, September 14, 2021. https://www.hudson.org/foreign-policy/pakistan-s-destabilization-playbook-khalistan-separatist-activism-within-the-us.

Pandya, Abhinav. "Bloom Review: How the West Finally Gets Its Views on Khalistanis Right by Examining Them Through Prism of Terrorism." Usanas Foundation, June 6, 2023. https://usanasfoundation.com/bloom-review-how-the-west-finally-gets-its-views-on-khalistanis-right-by-examining-them-through-prism-of-terrorism.

Mandair, Arvind-Pal S. Religion and the Specter of the West: Sikhism, India, Postcoloniality, and the Politics of Translation. Columbia University Press, 2009.

Mandair, A. P. S., Shackle, C., & Singh, G. (2000). Sikh Religion, Culture and Ethnicity. Taylor & Francis.

Singh, P., & Mandair, A. P. S. (2023). The Sikh World. Taylor & Francis.

Singh, P., & Fenech, L. E. (2014). The Oxford Handbook of Sikh Studies. Oxford University Press.

Milewski, T. (2021). Blood for Blood: Fifty Years of the Global Khalistan Project. HarperCollins India.

Ali, I. (2014). The Punjab Under Imperialism, 1885-1947. Princeton University Press.

Shani, G. (2007). Sikh Nationalism and Identity in a Global Age. Routledge.

Singh, G., & Shani, G. (2021). Sikh Nationalism: From a Dominant Minority to an Ethno-Religious Diaspora. Cambridge University Press.

Singh, G. (2000). Ethnic Conflict in India: A Case Study of Punjab. Palgrave Macmillan.

Singh, G., & Talbot, I. (1999). Region and Partition: Bengal, Punjab and the Partition of the Subcontinent. Oxford University Press.

Oberoi, H. (1994). The Construction of Religious Boundaries: Culture, Identity, and Diversity in the Sikh Tradition. University of Chicago Press.

Oberoi, H. (2022). When Does History Begin? Religion, Narrative, and Identity in the Sikh Tradition. State University of New York Press.

Kapur, R. A. (1986). Sikh Separatism: The Politics of Faith. Allen & Unwin.

Ballantyne, T. (2006). Between Colonialism and Diaspora: Sikh Cultural Formations in an Imperial World. Duke University Press.

McLeod, W. H. (2003). Sikhs of the Khalsa: A History of the Khalsa Rahit. Oxford University Press.